Role of Performer

“The harp is Ariadne’s instrument.”[1] If the harp is Ariadne’s instrument, can performers “become” Ariadne?

Roles of Harpists

Historically, harpists were employed for the entertainment of the nobility, orchestras and dances, but also worked notably as minstrels and story tellers. There was no notable discrimination of gender for ancient harp players, but there was perhaps a greater popularity for male players.

Popular perception of the harp throughout the 19th century, however, was that it was “an instrument especially intended for women,”[2] and that there was no possibility of harp music or harpists being able to compete with the more powerful, masculine, piano. Although a harpist himself, Théodore Labarre went so far as to say that harpists battle with an “impossibility of rendering energetic and passionate effects in a concert hall”[3], and that the harp could only be rendered seductive in a salon.

Ignoring for a moment the problems that arise with pairing female musicianship with seduction there is some truth in the difficulty of the 19th century harp “competing” with pianists, as harpists would have been performing on lightly strung single action harps (for description, please see development of the harp). This became less of an issue with the invention of the more powerful double action harp. The rise of the double action increased harmonic capabilities and created possibilities to play more demanding music.

The harp may be one of the only matriarchal instrument groups in western classical music. Whilst, in my opinion, this is truly exciting in a musical landscape where men still dominate top orchestral positions, this perhaps fuels the stereotype of harpists as graceful, genteel, fragile and angelic women, despite attitudes evolving throughout the 20th century. Non-musicians, who I have spoken to, always seem to be surprised upon hearing about the existence of male harpists, despite them forming the ranks of many of the top orchestral harp sections. It is unsurprising then that accounts of the Theseus myth also portray Ariadne in the light of the weak female.

I often find myself examining the importance of what we do as musicians, especially when looking at the world at large. What is the value in music when one could be an activist, doctor, or human rights lawyer? The value is in storytelling, and in reminding everyone what is beautiful about the earth and humanity. Story telling at its core is one of the most important roles in our culture. Indeed, Bruno Bettelheim notes that humanity’s “greatest need and most difficult achievement [is] to find meaning in our lives[4]” and highlights the importance of myths and fairy tales in providing people with a moral education. Importance also lies in providing stories of magic and escaping the mundane.

To perform this suite the performer inhabits Ariadne, tells her story, and subverts stereotypes throughout the suite to create a new narrative. Performers might therefore have a willingness to step outside of their regular concert persona, donning the guise of minstrel. The line between harpist and character becomes blurred. So, how might one do this?

Visuals and Choreography

The harp is a highly visual instrument, with the connection between harp and harpist as direct as possible, with no intermediary mouthpiece or bow between musician and string, where the sound is created. The setup for The Crown of Ariadne already provides the audience with a visual claustrophobia, as the harp is “trapped in a cage of percussion.”[5] This obscures the view of the harpist – just as Ariadne is obscured in popular culture and literature. This suite presents a different angle of the character and allows audience members to create their own picture of Ariadne and re-examine preconceived notions. The performer treats Crown as a theatrical piece, such as Stockhausen Harlekin (for dancing clarinettist) or Folke Rabe Basta for solo trombone. In these pieces movement is used to aid and enhance audience perception, and the performer approaches the piece as an actor and dancer in addition to their primary role as musician.

The score for Crown includes several scripted choreographic movements.

In Patria V, Crown is used to accompany Ariadne’s dancing (for further explanation please see Patria). The harpist embodies Ariadne in the suite and in the preface to the suite, Judy Loman notes, “In a sense the harpist is also a dancer, performing with ankle bells in Ariadne’s Dance and indulging in various elaborate gestures with the percussion instruments which also suggest choreography.”[6] How to balance this to avoid it feeling contrived is a challenge; “all events are minor, though they may have seeds of intention to them.”[7] I feel each individual performer must interpret the movement how it feels most natural to them, but to consider how to combine the movement with their intended meaning.

In Ariadne Awakens, for example the movement from harp to bell tree requires the harpist to stretch to reach the percussion instrument. If the performer has in mind that Ariadne is waking up, then naturally one might inhabit more of a purposeful stretching movement to reflect this, but it doesn’t necessarily need anything extra, just to connect the story to the necessary movements. In Schafer’s description as to why he chose dance as the primary medium for Patria V, he says “I want it [movement] to be sensed physically, proprioceptively, as if foaming out from the body rather than trickling down from the mind as a textbook memory.”[8]

Minimal Choreography

With stretching intention

Movement aids audience perception. As a performer you have the power to guide audience’s attention between instruments and create a homogenous experience. As Wagner said, “to the eye appeals the outer man, to the inner the ear.”[9]

Here is a moment in Ariadne Awakens where there are multiple ways of interpreting the choreography.

The lines might suggest literal shape of arm movement, flowing up and down. However, to me this feels very extraneous, and slightly over exaggerated. One might wonder if this dictation is more to show the length of time the movement should take, and so the amount of consideration one should put into the movement, so that one should not throw the movement away but lean into the ceremonious nature of the piece. After all, Ariadne was a high priestess of the labyrinth. Please see below for excerpts from a practice session, showing a literal interpretation and my eventual conclusion for my personal movement. The differences are externally fairly subtle but feel very different, illustrating how it is helpful to lean into what is comfortable for each individual performer.

Below I have included another clip from a practice session including another example of choregraphed movement from Sun Dance.

Influence of Salzedo

The relationship between sound and movement is a core part of Carlos Salzedo’s harp school. Born in France in April 1885, Carlos Salzedo moved to the USA at the age of 18 and established his harp method, which was particularly preoccupied with the aesthetics of movement in harp playing. He believed that as the harp was such a grand instrument, playing it should stylistically complement its grandeur, and that movement must be both functional and aesthetically pleasing.[10] Vaslav Nijinsky once said, “Salzedo’s hands explain the music before it starts.”[11] Salzedo expounded this idea to his students, and offered them advice on how to be aesthetically pleasing in their performances.[12] He also encouraged notating movement within the score, arguing that every movement must have definition.

With Salzedo technique, neither wrist rests on the sound board, and the approach to the string is more direct. Rather than preparing the string by squeezing it, Salzedo approach creates a brighter immediate sound. After playing, Salzedo players often release their hands upwards at the end of a phrase, both for relaxation and appearance.

This school of thought contrasts with my own training, in which I have been encouraged to conserve extraneous movement in favour of directing energy to the fingers and accuracy, but I have found it helpful to set that aside in order to enter the spirit of the piece.

Judy Loman, for whom the suite was written, was a pupil of Salzedo’s, and so Salzedo’s visible influence in the score is perhaps no great surprise. Many of the techniques employed such as “oboic flux”, “aeolian rustling” and “plectric sound” could have been lifted straight out of his method book. As a harpist who has no background in Salzedo technique, I had to research what these poetic directives meant.

Salzedo techniques employed in the piece are as follows:

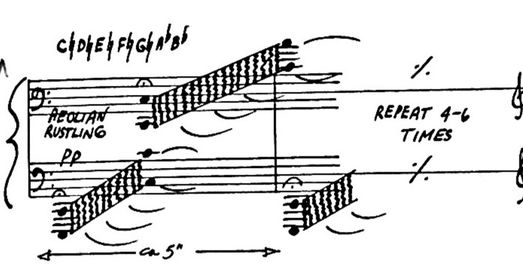

Aeolian rustling – The hands are drawn across the strings, pressing into them with fingers closed (seen in Sun Dance)

Rolling Surf - The hands are drawn across the strings, pressing into them with fingers open (seen in Sun Dance)

Aeolian Rustling - Hand upright with fingers splayed scrub across strings

Oboic flux – Glissando close to the soundboard, sonority at its best when played mezzo forte and not too slow (seen in Dance of the Night Insects)

Xyloflux – same principle as falling hail, but played as close as possible to the sound board (i.e. Ariadne Awakens)

Gushing chords – fortissimo rapid glissandi in direction of arrow (as seen in Sun Dance)

Falling hail – descending arpeggios using the backs of the finger nails, usually played piano or pianissimo (seen in Dance of the Bull)

Plectric sounds – play the strings with nails close to the sound board (i.e. Ariadne Awakens)

Thunder effect – glissando rapidly through the wire strings, causing them to clatter together (i.e. Dance of the Bull)

Timpanic sounds – one hand strikes the sound board in the most resonant part while the other plays the notated pitch. These should blend together to create one sound (i.e. Ariadne’s Dance)

Rocket like sounds/ fluidic glissandi - to slide a metal beater or tuning key along the string to achieve a pitch bend – fluidic glissandi go to specific pitches, where rocket sounds are played as rapidly as possibly for a shooting ascending sound (i.e. Dance of the Night Insects)

Tam tam – to hit the indicated string on the harp with a beater (i.e Sun Dance) [13]

One might also ask if harpists schooled in other techniques can perform the piece in the “correct way”. Rosanna Moore discusses this and raises the question, “Do the movements become contrived, unnecessary or even dangerous for the performer?”[14] I have experimented with playing the suite with as best Salzedo technique as I can manage, keeping my arms off the sound board, and practising Salzedo alignment, having considered that the technique does bear the most similarities to dance. For example, keeping both arms off the sound board mirrors a ballerina’s first position.

Swope, Martha, Ballet positions. Image. Britannica. October 3rd 2022. https://www.britannica.com/art/first-position

I have decided, however, that personally this does not work. Too much mental capacity is used to maintain the height of my arms etc, so all my movements become over thought and contrived, distracting from the fundamentals of the music and expressively embodying Ariadne. A compromise might be made between a performer’s own training and creating dance movement for the piece. Performers might also ask themselves how much they want to explain to the audience through their movement. Do they want them to be visually informed of what music is about to happen or shocked? How extraneous should the movement be? I feel that the movement cannot be prescribed, just interpreted as serves each individual best, for their individual interpretation of Ariadne.

Next suggested navigation: Role of the Audience

[1] R. Murray Schafer, Patria, The Complete Cycle, Ontario: Coach House Books, 2002.p.162

[2] Temina Cadi Sulumuna, “The Harp in Early 19th Century French Culture”, in Rethinking the Musical Instrument, edited by Mine Doğatan Dack, 122-141, Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022.p.123

[3] Dack, “The Harp in Early 19th Century French Culture”, in Rethinking the Musical Instrument p.131

[4] Bruno Bettelheim, The Uses of Enchantment, The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, London, UK: Penguin Books, 1991. p.4

[5] Rosanna Moore, “Choreography in R. Murray Schafer’s The Crown of Ariadne – Technical or Theatrical?”, Contemporary Music Review, Vol. 38, no.6, (2019): 623 – 643, accessed 25th July 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2019.1706348p. 625

[6] R. Murray Schafer, The Crown of Ariadne, Ontario: Arcana Editions, 1980. p.0

[7] Schafer, Patria, The Complete Cycle, p.117

[8] Schafer, Patria, The Complete Cycle, 154

[9] R. Murray Schafer, The Soundscape: Our Environment and The Tuning of the World, Ontario: Destiny Books, 1993. p.11

[10] Moore, “Choreography in R. Murray Schafer’s The Crown of Ariadne – Technical or Theatrical?” p.626

[11] Dewey Owens, Carlos Salzedo, from Aeolian to Thunder, Chicago: Lyon and Healy Harps, 1992. p.47

[12] Moore, “Choreography in R. Murray Schafer’s The Crown of Ariadne – Technical or Theatrical?” p.627

[13] With thanks to Eleanor Turner

[14] Moore, “Choreography in R. Murray Schafer’s The Crown of Ariadne – Technical or Theatrical?” p.625